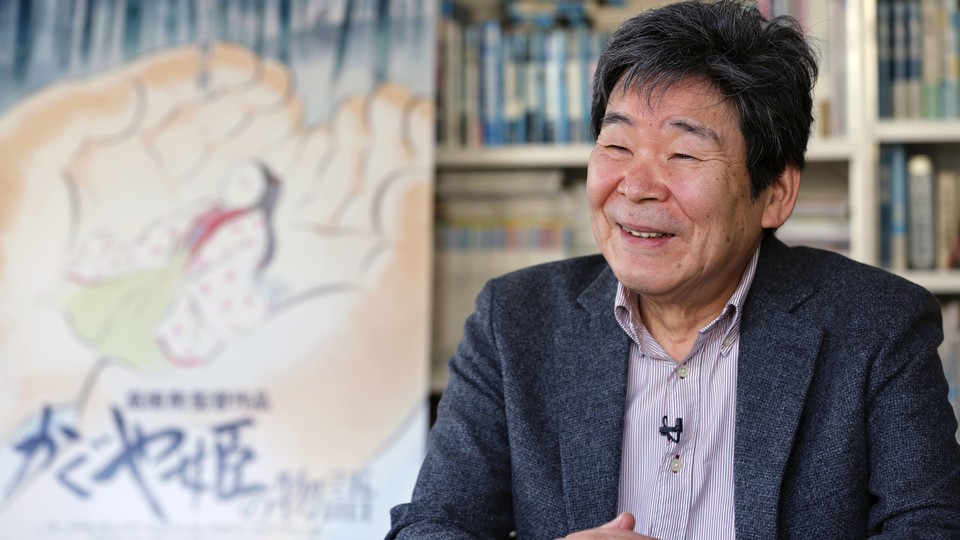

Remembering Animation's Legendary Isao Takahata

The renowned Japanese director, who has died at age 82, helped found Studio Ghibli and made films like Grave of the Fireflies.

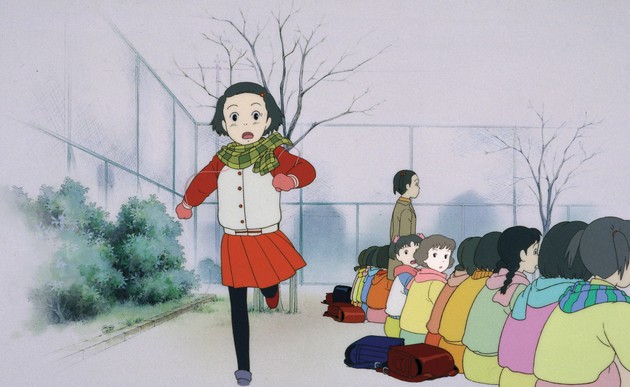

Much of Isao Takahata’s 1991 animated film Only Yesterday is told through vivid recollections: Its Japanese title, Omoide Poro Poro, literally means “memories come tumbling down.” The protagonist, Taeko Okajima, is a 27-year old woman heading to the Japanese countryside on vacation when she is idly struck by memories of her 10-year-old self, formative stories and events that take on new meaning for her in hindsight. The present-day scenes are animated realistically—the characters are less cartoonishly expressive, their facial muscles given greater detail. Meanwhile, the flashbacks are more plainly drawn, with unfinished backdrops rendered in a hazy, half-remembered glow.

In one scene, young Taeko walks home past a boy who, according to some of her giggling schoolmates, has professed that he has a crush on her. Blushing, he stammers out a question: “Rainy day or cloudy or sunny day, which do you like?” She pauses to consider as he stares at his shoes, then replies, “Cloudy,” to his delight. “Me too!” he yells, walking off triumphantly. Taeko runs toward her home, and as she does, she trots into the sky, a burst of magic in a moment that’s otherwise naturalistic. It’s the kind of scene that could only be executed by Takahata, one of the founders of the legendary Studio Ghibli, who time and again mixed the impressionistic joy of animation with an unusually tight grasp on realism and the nuance of human relationships.

Takahata died of lung cancer April 5 at the age of 82, according to a statement from Ghibli. Though he was never quite as renowned (particularly in the U.S.) as one of the studio’s other founders, Hayao Miyazaki, Takahata’s smaller body of work still stands as some of the most impressive filmmaking in the history of animation—a feat that’s all the more fascinating given his background. Having graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1959 with a degree in French literature, Takahata was never an animator himself. By his own admission, he couldn’t even draw. But he was constantly interested in bending the medium, often adopting radically different visual styles from project to project (or, in the case of Only Yesterday, within the same film).

In the 1960s, Takahata worked at Japan’s hugely popular Toei Animation, mostly as an assistant director for TV and movies. There, he met Miyazaki, who like him chafed under the company’s rigid hierarchy. When Takahata got the chance to direct his own film for Toei, 1968’s The Great Adventures of Horus, Prince of the Sun, it was a flop that the company saw as too adult and violent. Now, though, it’s regarded as a groundbreaking entry in Japanese animation. When making the movie, Takahata had set his sights beyond traditional children’s fare. “This was the greatest joy for me and for the entire staff who had unstintingly poured their talents into the project,” Takahata later said, reflecting on the appreciation Horus eventually received. “[Toei] should have aimed this film toward high-school and university students and young adults, those who had not been interested in animation films. But the company made no efforts to do so.”

Takahata left Toei in 1971 and bounced around from company to company, often still collaborating with Miyazaki. In 1985, the pair helped form Ghibli based on the success of Miyazaki’s recently released Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Takahata’s first film for the company was his World War II drama Grave of the Fireflies, released in 1988 as part of a double feature with Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro. While Totoro was an instant, beloved children’s fantasy classic, Grave of the Fireflies was a much more complex, upsetting work, a sober retelling of the last months of the conflict from the perspective of two Japanese children.

In depicting the firebombing of Kobe, Takahata drew on his own childhood memories, which helped make Grave one of the most stark World War II films made in any medium to this day. (It’s wrenching enough that I find it difficult to rewatch.) Though Takahata would never make another movie that was quite as devastating, Fireflies did establish his reputation as the more grounded of the two Ghibli giants. His follow-up, three years later, was Only Yesterday, my personal favorite of his canon and certainly the most underrated of all the studio’s films.

Only Yesterday isn’t nearly as bleak as Grave of the Fireflies, but it does, once again, seem less obviously aimed at children—even though half of its action is centered on the younger version of Taeko as she navigates puberty, family drama, and young love. It’s a melancholy tale that presents Taeko’s memories with swooning romanticism (in an old-fashioned anime style, drawn in a nearly heavenly light), but also probes past the surface to find subtleties she didn’t understand as a child. Only Yesterday went on to be a surprise box-office hit in Japan. But Disney (which at one point owned the American rights to Ghibli movies), didn’t release it in the U.S. until 2016, a move some critics have attributed to Only Yesterday’s discussion of issues like menstruation.

Takahata’s other ’90s movies were more fanciful. Pom Poko (1994) is an environmental allegory dressed up as a children’s film about anthropomorphic, shapeshifting raccoons; it was a colossal hit in Japan. My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999) is an adaptation of a Japanese comic strip, drawn to look like a simple, stylized watercolor. It’s a charming work, presented as a series of whimsical vignettes poking fun at the family unit. But coming in between Miyazaki’s immense box-office smashes Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, My Neighbors the Yamadas was a financial disappointment for Ghibli. Takahata retreated to producing and mentoring other artists for the next decade, while he slowly put together his final (and most massive) project.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), based on a 10th-century Japanese folktale, is a visually flabbergasting work drawn in fluid charcoal strokes and watercolors. Recalling an old painting that has come to life, the film is stunning and elegiac, representing a millennia-old world through advanced animation techniques. Though it’s a mythic story (in which a family finds a young girl growing inside a glowing bamboo shoot, and eventually raises her into a life of nobility, with tragic consequences), its characters feel genuine. That was Takahata’s finest skill as an artist: his ability to draw out the humanity in the most spellbinding of images.

“I’m not saying fantasy is bad. I myself enjoy the genre from time to time. However, I don’t agree with getting an audience excited by seeing a character do something incredible that defies logic,” Takahata said in a 2015 interview. “Too many films these days feature characters who overcome difficulties using nothing more than the power of love.” His movies resisted those simple notions, appealing to viewers not through tales of invented triumph, but rather by speaking to the deepest parts of their imagination.

This vision came through in Takahata’s writing and his visuals, which always relied on a hand-drawn look. In defending two-dimensional animation (over the CGI approach favored by companies like Pixar), Takahata said, “By keeping everything flat, animation allows viewers to imagine what is behind the images.” There is plenty of visual beauty to behold in each of his films, but it’s what’s going on behind them that made Takahata such a titan of both animation and cinema.