Gene Deitch, Cartoon Modernist Who Headed UPA New York And Terrytoons, Dies At 95

Gene Deitch, one of the last of the major figures who worked during the Golden Age of American animation, passed away last night in Prague, Czech Republic. He was 95 years old.

According to a family friend and neighbor, the cause of death was not related to coronavirus. While Deitch hadn’t been sick, he had complained about intestinal problems in the days before his passing.

One of Deitch’s last Facebook posts from last weekend was about the coronavirus. He wrote:

Most of us old folks now still managing to live in the first quarter of this muddled century, widely considered to be the twenty first, are suddenly forced to think about what is realistic, outside of the previous rosy commercial concepts of the industrial futurists.

Just for one thing, my own prediction is that the next fashion statement will be a revival of the middle ages face mask; this time with medicated meaning / matching shirt/ blouse/ facemask sets, the return of spangles, flourescent, electric, color blinking facemasks, musical and saucy statement face masks, steamy statements migrating from t-shirt breasts to breathing. Wait for it! Tragedy can surely be monetized!

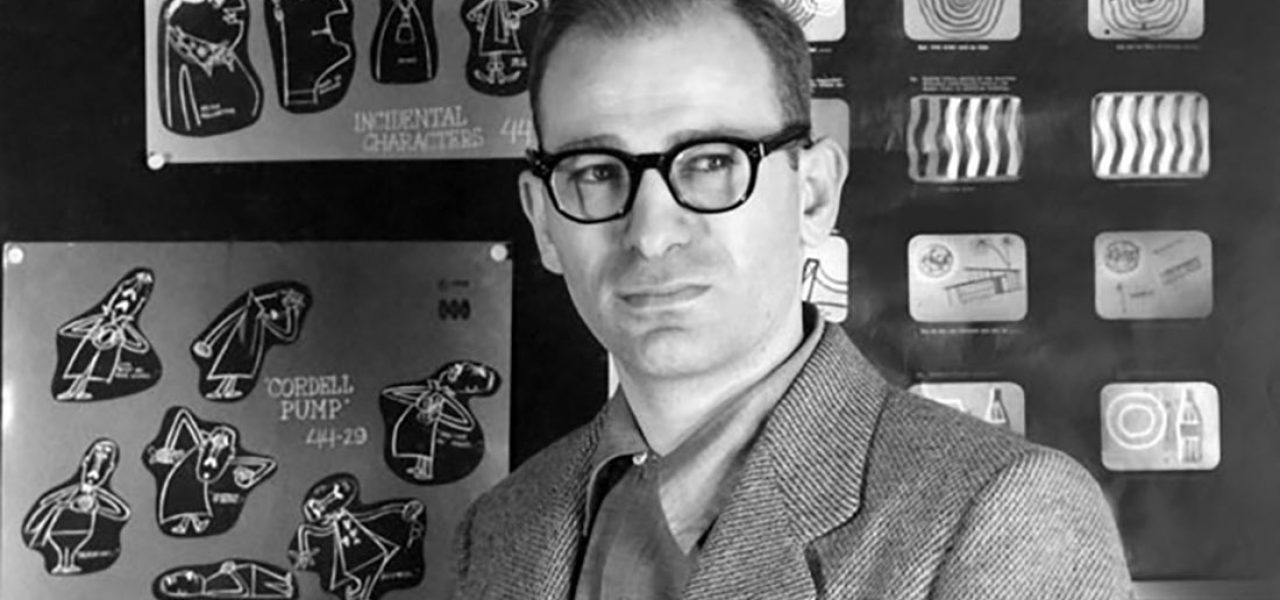

Gene Deitch was born Eugene Merril Deitch on August 8, 1924 in Chicago, Illinois. In 1942, he started his art career straight out of high school as technical illustrator at the North American Aircraft plant in Los Angeles. Following World War II, he was hired as an assistant art director at CBS Radio.

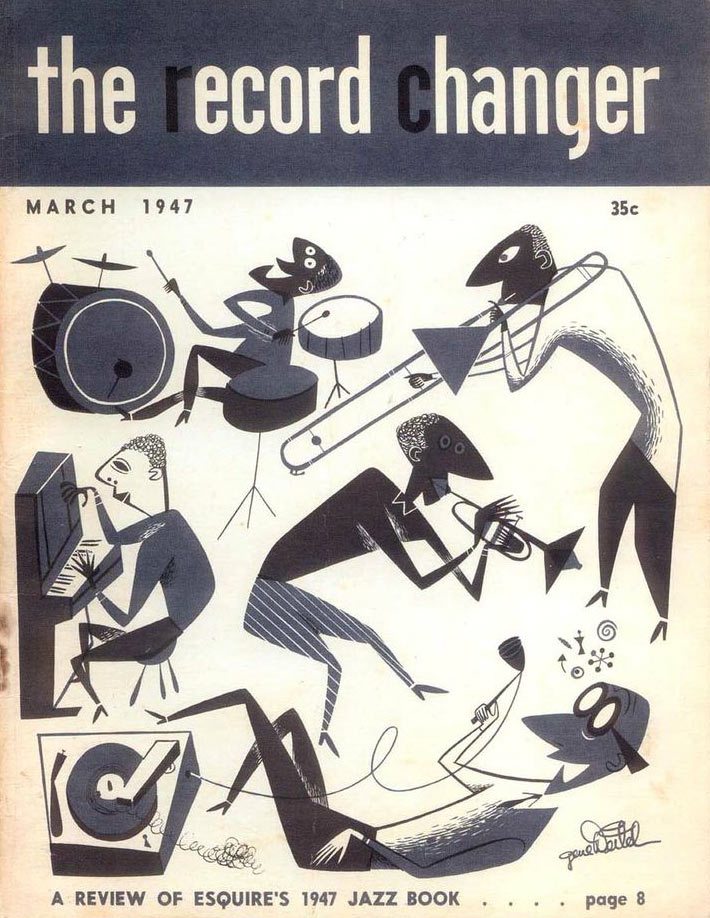

While working at CBS, he had a side project: drawing cover illustrations and interior comics for The Record Changer, a specialty publication aimed at traditional jazz record collectors, and it was these stylized cartoon drawings that caught the attention of artists at United Productions of America (UPA), a fledgling animation company started by ex-Disney Studio strikers. Deitch was hired at UPA in 1946, among the first dozen employees at the company, and became a protégé of John Hubley and Bill Hurtz.

In 1949, Deitch moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he directed his first professional films at the Jam Handy Organization, an industrial film producer that counted General Motors as its largest client. His work at Jam Handy was interrupted when he was invited to rejoin UPA, this time at its new studio in Manhattan.

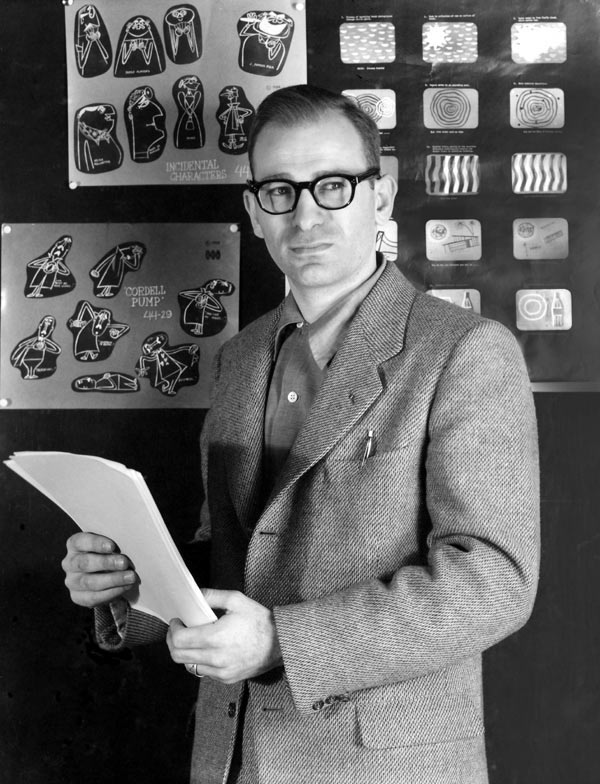

While he initially joined UPA-NY as a production designer in mid-1951, he soon took over as creative director, leading the studio during its heyday as one of the most recognized and critically lauded producers of animated tv commercials in the United States.

Deitch left UPA in 1955 to become the creative director at CBS-owned Terrytoons, where he led an amazing turnaround for the struggling animation studio. Against all odds, he turned the schlocky producer of Mighty Mouse and Gandy Goose into a respectable producer of modern cartoon shorts. “It was the dream challenge of every red-blooded 100% American boy animator; a chance to remake the world’s worst animation studio into the best,” he said of the experiment, which last only a few short years.

In my book Cartoon Modern, I described the situation when Deitch arrived at Terrytoons:

The studio, in the NewYork City suburb of New Rochelle, was in such sorry run-down shape that CBS kept delaying taking Deitch to the studio during negotiations. When he first arrived at the studio, his first order of business was to simply create better working conditions for the Terrytoons artists. With the support of CBS, Deitch had the studio repainted, bought new furniture, and gave inkers and opaquers their own cubicles to work in (replacing the sweatshoplike arrangement of long rows of desks). A state-of-the-art projection system and new animation cameras were also installed. Deitch redesigned the Terrytoons logo and created a title card—signed by every staff member—which appeared in front of the films, a gesture meant to show his appreciation for each artist’s contribution. In another gesture of goodwill, Deitch promised not to fire any of the artists, instead opting to construct his modern vision around the studio veterans. He augmented the existing crew with as many like-minded young artists as he could, including Jules Feiffer, Tod Dockstader, Al Kouzel, Ray Favata, Ernie Pintoff, and Len Glasser.

Deitch reflected on his goal for Terrytoons in 2001:

My overriding goal was to reinvent Terrytoons, to create a new reputation, to win the support of the disgruntled staff, to revise, where practical, films in production, without interrupting workflow, and mainly to rebuild the story department, bringing in fresh talent such as Jules Feiffer and Al Kouzel, to inspire Tommy Morrison, Larz Bourne, Eli Bauer, and others already on the story staff; to venture into fresh territory. I spent most of my own time in there with them; it all had to start with story and characters.

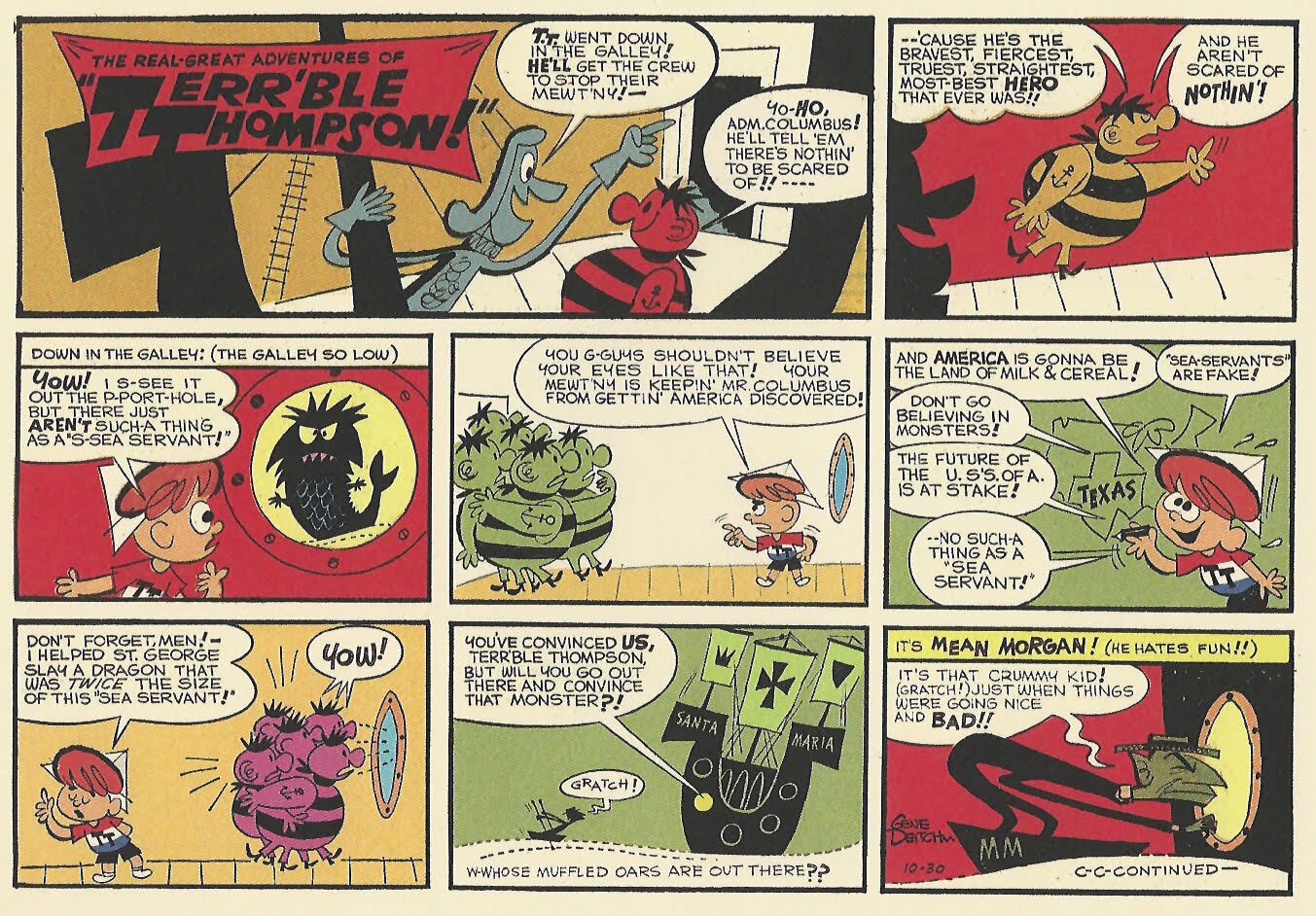

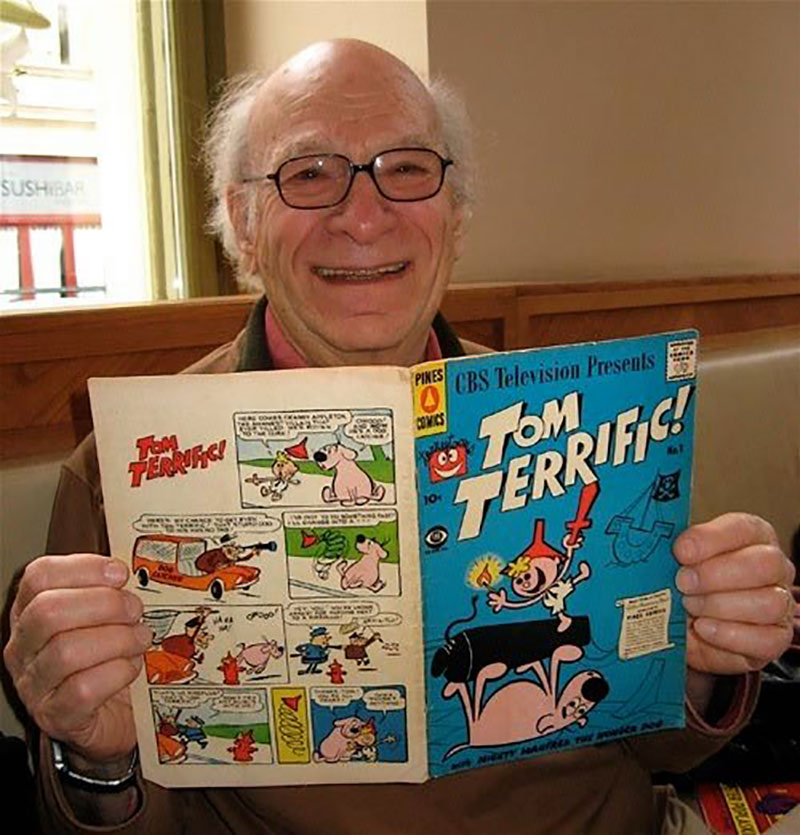

At Terrytoons, Deitch created the popular 1950s tv character Tom Terrific, which aired as a series as part of the Captain Kangaroo tv series, and oversaw a slate of new theatrical cartoon characters, including Sidney the Elephant, Clint Clobber, Flebus, and John Doormat.

Fired from Terrytoons in 1958, he set up his own studio, Gene Deitch Associates. A client, Rembrandt Films, offered to fund a short he wanted to make, an adaptation of Jules Feiffers’s comic Munro, if he would help fix some of their existing productions in Communist Czechoslovakia. Deitch agreed to travel behind the Iron Curtain for a ten-day trip, but remained there for the rest of his life, in the process becoming one of the only Americans to live full-time in the country until its transition to a democratic state began in 1989. Incidentally, that first project, Munro, became a big success, earning him an Oscar for best animated short in 1961.

Deitch recounted the story of living in Communist Czechoslovakia as an American, and later in the Czech Republic following the Velvet Revolution of 1989, in his memoir For the Love of Prague. The story was also related in this documentary:

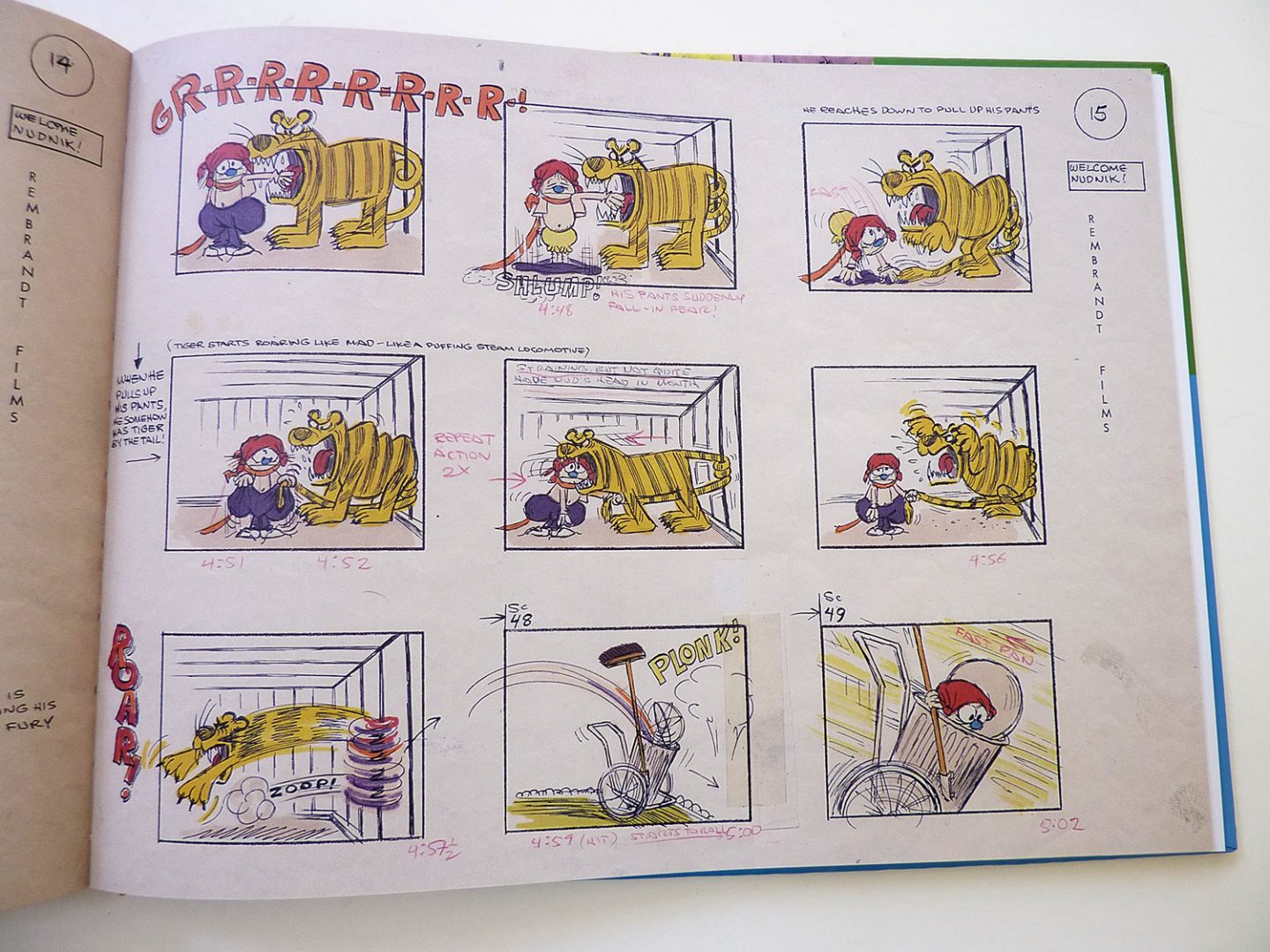

At the Czech studio Bratri v Triku, Deitch directed hundreds of films over a 50-year period, primarily working on animated adaptations of children’s books for the American company Weston Woods Studios. He would earn three more Oscar nominations: Self Defense—For Cowards, Here’s Nudnik, and How to Avoid Friendship, the latter two nominations both occurring in the same year, 1965.

The character of Nudnik, created by Deitch, was featured in 12 shorts produced for Paramount in the mid-1960s. But it was another series of shorts that earned Deitch infamy from cartoon fans. In the early 1960s, he directed a series of 13 Tom & Jerry shorts for MGM while living in Czechoslovakia.

The Tom & Jerry shorts didn’t compare favorably to the MGM films and were notorious for their lack of faithfulness to the original shorts produced in Hollywood by Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera. While they have achieved a cult following in more recent years, and have even been collected on a dvd release, the story of how they were made is more interesting than the actual cartoons. It was not known for many years that the shorts were actually produced in Eastern Europe with extremely limited resources by people who had never seen any of the original cartoons. Deitch wrote about his experience with these films at length a few years ago:

I am painfully aware that my Tom & Jerry cartoons were savaged by most of the critics and hardcore H&B fans. I was the first animator to continue the series, and obviously I was in the line of fire. I had every possible disadvantage in producing these shorts; 1. my own negative T&J feelings at the time. 2. working in a foreign country, with the first non-USA, studio ever to tackle this hyper-American series, with a crew that was creatively isolated; way out of the helter-skelter, crash-bang American T&J cartoon culture, and 3. with a dollar budget half the amount of the original MGM series. Not only had no one in the Prague animation studio ever even seen a Tom & Jerry cartoon, but I had never tried to draw the characters! They were out of my way of drawing. I did admire the skill of the Disney shorts, and I was a great fan of the brash comedy of the Warner Brothers output. But as gross as many of the [Hanna Barbera] cartoons were, the outrageous pain the Tom and Jerry characters inflicted on each other did make me laugh out loud.

Below are just a few of the other shorts that Deitch made at Bratri v Triku, and a much better way of judging the output during the second half of his career than the Tom & Jerry films. The Hobbit was a test piece, not intended to be seen by the public, for an unproduced theatrical version of the novel by J. R. R. Tolkien.

MUST-SEE: 1977 doc in which Gene Deitch describes his process of adapting an illustrated children's book into an animated short. A great insight into animation production that is intimate & handcrafted with custom solutions for creative challenges. https://t.co/jKT6A4iLRp pic.twitter.com/HcAWnPvPgf

— amid amidi (@amid) April 18, 2020

Deitch had extensively documented his life and work on his personal website GeneDeitchCredits.com.

He is survived by his wife, Zdenka Najmanova, and three sons from his first marriage, Kim, Seth, and Simon.