/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72943901/ghiblispread_StudioGhibli_ringer.0.jpg)

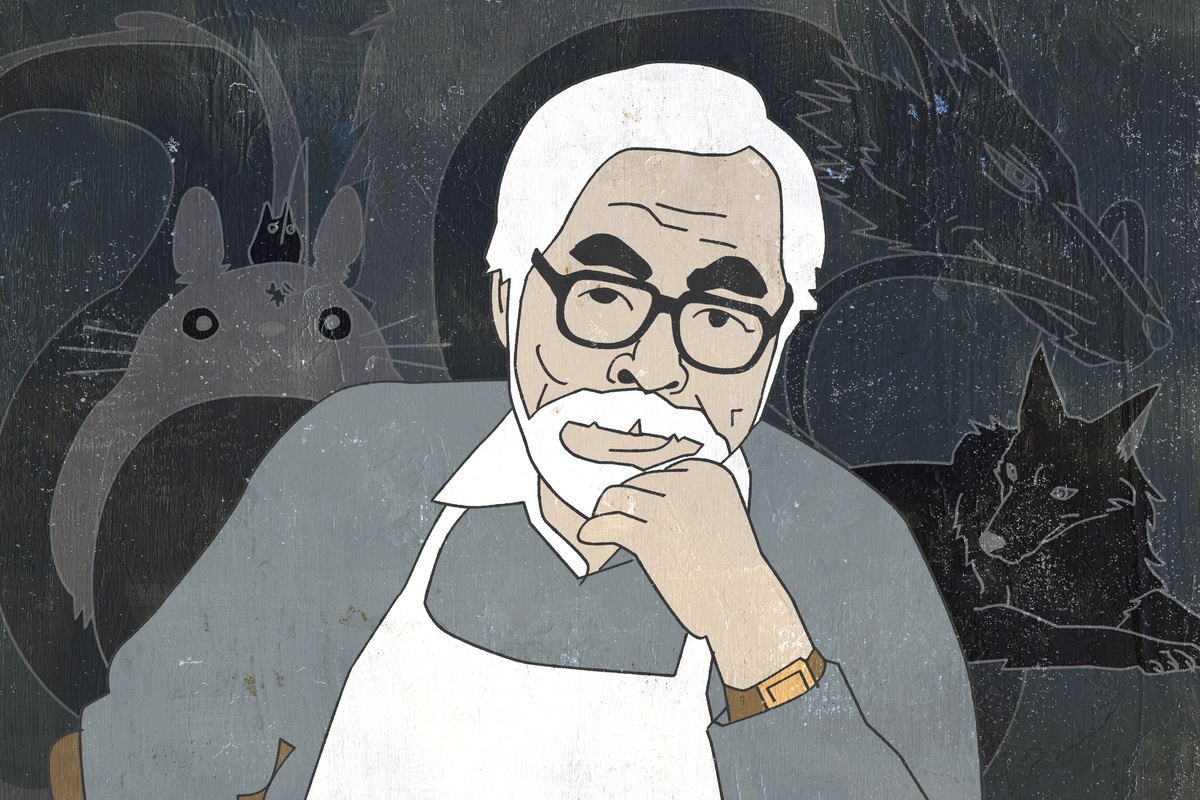

In 1984, Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind premiered in Japan. Based on the manga that Miyazaki had started two years earlier for Tokuma Shoten’s Animage magazine, Nausicaä was only the second feature of Miyazaki’s animation career. It’s a remarkable film that earned critical acclaim and commercial success, but the company that produced the film, Topcraft, went out of business soon after its release. Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who was something of a mentor to Miyazaki and also the producer of Nausicaä, were already widely respected veterans of Japan’s animation industry. Yet no production company was willing to take on the costs of their next film. And so, along with producer Toshio Suzuki, they started a company of their own: Studio Ghibli.

Studio Ghibli was thus born out of necessity. For Miyazaki and Takahata, founding the studio was a crucial step toward achieving the independence they craved, as parent company Tokuma Shoten largely left Ghibli to its own devices. Until then, the animation auteurs had been held back only by the limitations of their era, forced to work within the traditional confines of a medium that still struggled to escape the boundaries of TV. Together, with the business savvy of Suzuki to guide their works to prosperity, Studio Ghibli would forever change the world of animation.

In 1995, 10 years after Ghibli’s creation, Suzuki delivered a speech at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival in which he reflected on the studio’s original mission:

Ghibli’s goal has been to devote itself wholeheartedly to each and every film it has undertaken, not to compromise in any way whatsoever. It has done this under the leadership of directors Miyazaki and Takahata, and by adhering to the tenet that the director is all-powerful. The fact that Ghibli has somehow been able to maintain this difficult stance for 10 years, to realize both commercial success and proper business management, is due to the exceptional ability of these two directors and the efforts of the staff. This can be said to be the history of Studio Ghibli. …

To make something really good, that was Ghibli’s goal. Maintaining the existence of the company and seeing it grow were secondary considerations. This is what sets Ghibli apart from the ordinary company.

Almost 40 years after it was founded, Studio Ghibli has become a global brand—yet it remains no ordinary company. Its reach has long extended beyond the islands of Japan, as the visionary works of Miyazaki and Takahata, as well as those from the likes of Yoshifumi Kondo and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, have spread across the world. Ghibli’s production scope has widened to include a museum, a theme park, and a small merchandising empire. Yet the studio, forever seeking to strike a balance between art and just enough commerce to stay afloat, has never lost sight of its promise to prioritize its films and the audience’s experience.

On Friday, Ghibli released the 12th film in Miyazaki’s impeccable filmography, The Boy and the Heron, in theaters across the United States. It’s yet another stunning visual and storytelling achievement from one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers, and it’s arriving at a time when Miyazaki’s—and Studio Ghibli’s—popularity is experiencing rapid growth in the U.S. after slowly building for years.

In 1996, Steve Alpert was hired by Studio Ghibli to start up its new international division. An American who had been working in Tokyo for 10 years, most recently for Disney, Alpert had been selected by Suzuki to help grow Ghibli’s international audience. For the next 15 years, Alpert would play a pivotal role in the studio’s global ascent. “Studio Ghibli would still be probably the same Studio Ghibli without international distribution,” Alpert tells The Ringer. “But when Mononoke Hime [Princess Mononoke] came out, that really changed everything.”

It may be hard to imagine today, but Studio Ghibli once struggled to draw audiences in theaters—even in Japan, to a certain extent. In the years leading up to Princess Mononoke’s release in the summer of 1997, the box office success of Ghibli’s films had finally been catching up to their critical acclaim after a relatively slow start. Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky (1986) and the 1988 double bill of Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro and Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies had failed to produce the same theatrical revenue that Nausicaä had. But starting with the massive success of Kiki’s Delivery Service in 1989, Suzuki had begun investing more money and effort into advertising Ghibli’s films, and Only Yesterday, Porco Rosso, and Pom Poko followed suit in becoming commercial hits.

Princess Mononoke, however, propelled the company to unprecedented heights at the Japanese box office, drawing the attention of the international media in the process. The film grossed more than 19 billion yen ($160 million) to far exceed the earnings of the previous record holder in Japan, Steven Spielberg’s E.T., which had held the box office crown since 1983.

Not long before Alpert’s arrival at Ghibli in 1996, the studio had formed a partnership with the Walt Disney Company that gave the latter worldwide distribution rights to Ghibli’s films. Disney’s global reputation would prove to be crucial to Ghibli’s growth outside Japan in the years to follow. Another big factor was the emergence of home video.

Before Disney, Ghibli had achieved modest success with the U.S. VHS release of My Neighbor Totoro through Fox Video in 1994, but the studio, and Miyazaki in particular, were still wary of licensing films abroad after their previous problems exporting Nausicaä. In the ’80s, Nausicaä was licensed to an international distributor by Tokuma Shoten, and it was crudely edited into a version of the film that was rebranded as Warriors of the Wind. In Disney, Ghibli gained a partner with an even stronger grip on Japan’s home video market than Tokuma’s own company had. And crucially, Disney was willing to agree to Ghibli’s terms.

“It used to just be, do your best doing the movie, and you can license to TV and stuff like that, but that’s it,” Alpert says of the pre-VHS industry. “You don’t make a lot of money, except for a few exceptions. But once home video kicked in, boom, that’s a whole different thing. And that’s where Ghibli started going outside of Japan while that was happening. The other thing is Disney said they wouldn’t cut or alter the films, which was a big deal. Ghibli wouldn’t have allowed them to distribute otherwise.”

Disney had timed its deal with Ghibli perfectly: The company gained the opportunity to distribute Princess Mononoke ahead of the movie’s record-shattering commercial success and as Miyazaki’s fame began crossing borders. Yet this union didn’t exactly pan out the way everyone had expected. “Lots of foreign people got interested [after Princess Mononoke], but Disney was ahead of that,” Alpert says. “Disney had already signed up for the film. They had no idea what the film was going to be like. They thought they were getting another My Neighbor Totoro.”

Rather than receiving the type of family-friendly film that centers on a massive, cuddly woodland spirit, Disney had taken on a project that would be a departure from what Miyazaki’s typical style and subject matter were perceived as. Set in Japan’s Muromachi Period, Princess Mononoke depicts a bloody conflict between humans and the gods of the forest. It features clashing samurai, severed limbs, and, within the movie’s opening minutes, a giant boar’s guts spilling out across the screen.

Alpert still remembers the reaction of Michael O. Johnson, then the head of Disney’s international business, when he saw early snippets of Princess Mononoke for the first time. “The movie wasn’t finished, but [Ghibli] had a rough trailer,” Alpert recalls. “We showed it to him, and there’s arms being cut off, heads being cut off, and the heroine has blood all over her mouth. And he’s horrified, thinking, ‘This is it. My career with Disney is over. I’ve signed up for this film, and now they’re obligated to distribute it.’”

When Princess Mononoke was later released in the United States, it was done under Disney’s new subsidiary at the time, Miramax, to distinguish its mature content from the House of Mouse’s more family-oriented brand. But the dissonance between the visions and sensibilities of Disney and Ghibli couldn’t be bridged that easily. All sorts of issues plagued the partnership over the years, many of them boiling down to Disney’s persistent desire to Disney-fy or otherwise alter Ghibli’s works to make them better suited (or so the Mouse imagined) for an American audience. At one point, Disney even decided it would be better off just holding on to the vast majority of Ghibli’s catalog of films rather than taking on the costs of distributing them via home video.

“Even considering all the problems we had with Disney, the other major theatrical distributors would’ve been worse,” Alpert says. “And the really good art house guys that really knew how to release an art house film didn’t want to do animation.”

Miramax didn’t make the North American distribution process for Princess Mononoke an easy one. Neil Gaiman was hired to write the English-language version of the screenplay—a truly inspired choice, as the British author had only recently concluded his legendary Sandman run. In Alpert’s 2020 memoir, Sharing a House With the Never-Ending Man: 15 Years at Studio Ghibli, he showers Gaiman’s original script with praise: “Things that were awkward in the direct translation from the Japanese were given back the power and the flow they had in Hayao Miyazaki’s original version.”

Yet Miramax made changes to Gaiman’s work without consulting him. At the behest of the company’s ill-tempered boss, Harvey Weinstein, the now-imprisoned former Hollywood executive and producer, Miramax kept trying to find ways to alter the film to maximize its appeal to an American audience. Alpert and Ghibli, in turn, would exercise their contractual rights to reject any alterations and resist Miramax’s persistent efforts to cut the film’s running time. As Alpert recounts in his memoir, Suzuki even presented Weinstein with a sword in New York, shouting, “Mononoke Hime, no cut!”

(After Princess Mononoke, Ghibli’s subsequent English-language releases would be handled by Disney and supervised by Pixar’s John Lasseter, who had long been a champion of Miyazaki’s works in the U.S. Based on Alpert’s recollections in his memoir, it seems as if these efforts went much more smoothly.)

In all, Princess Mononoke’s English-language release was a messy, arduous, and unnecessarily expensive ordeal, even though it ultimately yielded a satisfactory final product. The film failed to make much of a splash upon its initial release in U.S. theaters, but despite its lackluster box office performance abroad, Princess Mononoke’s commercial and critical success in Japan paved the way for the studio’s next major breakthrough: Spirited Away.

“In a way Princess Mononoke broke barriers, the initial barriers that maybe needed to be broken before Spirited Away could come on,” says Susan Napier, a professor at Tufts University who wrote the 2018 book Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art.

A beautiful, dreamlike masterpiece, Spirited Away follows the journey of the young Chihiro after her parents are suddenly transformed into pigs and she’s forced to navigate a magical realm where spirits and gods roam freely. When the film premiered in Japan in 2001, it eclipsed the box office record that Miyazaki had previously broken with Princess Mononoke and held the country’s highest mark for nearly two decades, until it was finally surpassed in 2020. In addition to its commercial success, Spirited Away remains one of Japan’s crowning artistic achievements in film, garnering critical acclaim like no other animated work before it (or, perhaps, even after it). It became the first (and only) animated film to win the Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin International Film Festival, and it won Best Animated Feature at the 2003 Academy Awards, among dozens of other major international awards victories.

“Spirited Away was a real turning point,” Napier explains. “Getting the Oscar, getting good distribution from Disney really made it seem like it was a film that people should see, not some strange art house film or trivial children’s entertainment. It really changed the way people perceive anime and Miyazaki in particular.”

Spirited Away had attained rarefied critical status in the international film community not only for a Japanese anime film, but for any Japanese film. “In the 1950s, ’60s, Japanese films were regulars at the film festivals outside Japan,” says Shiro Yoshioka, a professor at Newcastle University who has published articles and book chapters about Miyazaki and Ghibli in both Japanese and English. “For example, names like [Akira] Kurosawa were well known outside Japan. But after that, Japanese films were sort of kept on a low profile. In Japan itself, it was constantly overshadowed by Western films, especially Hollywood films.

“But this was huge news for Japanese film because this was one of the first Japanese films—after that [initial] crossover and that sort of age—that was truly successful outside Japan and that won this Academy Award,” Yoshioka continues. “So there was huge media hype in Japan that [Miyazaki is] great, and he’s the second crossover, and that sort of thing. And on top of that, the success of Miyazaki and Spirited Away was often associated with [the] general popularity and success of Japanese anime at that time.”

Despite Spirited Away’s international critical success and peerless box office performance in Japan, the film nonetheless struggled to attract much of a theatrical audience in the United States. When it was first released in the U.S. in September 2002, the film received a limited theatrical run with little marketing, and it grossed only $5 million. Even when it was brought back to American theaters following the Oscar honor, Spirited Away only doubled that total to finish with $10 million by September 2003. Although Lasseter, the since-ousted Pixar exec, played a major role in campaigning for the movie’s Oscar win, there’s a prevailing sense that Disney could have done much more to boost its profile for a more successful run in America.

Alpert tells me that “the Disney people [in America] didn’t want it.” As he recalled in Sharing a House With the Never-Ending Man, when Ghibli representatives traveled to Pixar in the fall of 2001 to screen the film for a number of Disney executives, Disney’s head of international film distribution, Mark Zoradi, told Alpert that they loved it, but that “everyone thinks it’s too Japanese, too … esoteric, and nobody in the U.S. will get it.”

Even with all of Disney’s shortcomings as a partner, its relationship with Ghibli helped establish a foundation for the studio to build on in the U.S. In Japan, Ghibli had already shifted the cultural perception of animation’s artistic value and potential profitability. But as the modest American box office performances of two of Miyazaki’s most revered works showed, there was still tremendous room for growth abroad.

“It wasn’t easy what [Ghibli was] trying to do, trying to break new ground, really, get people to accept animation as a medium,” says Alpert. “Not just for children’s entertainment, but in the sense that it’s like literature. It’s an art form, and that’s how they view it.”

“Ghibli films have been seen by a wide range of audiences worldwide,” Suzuki told The New York Times in 2020. “However, in the States, it wasn’t really working as we had expected. People would come to the theaters to watch Ghibli films on the East Coast and West Coast, but in the Midwest region, it was hard to get people in the theaters.”

Over the past decade, Studio Ghibli has been experiencing something of a renaissance in the United States, albeit one that has emerged slowly.

Long before New York–based distributor GKIDS acquired the North American theatrical distribution rights to Studio Ghibli works in 2011, and before GKIDS even became an actual company, its founder, Eric Beckman, began working with Ghibli. “He was the cofounder of the New York International Children’s Film Festival, which is the largest festival for kids in North America,” explains GKIDS president David Jesteadt. “They did a big Studio Ghibli retrospective around the year 2000, before Spirited Away. I think people forget in the scheme of things how fast some of this stuff has happened. Given the studio’s 40 years old at this point, it’s like the actual popularity in America is pretty compressed to some degree, going from the die-hard insiders to getting wider and wider. So [Beckman] played those films at the festival and got to know the international team over there.”

On Ghibli’s side, Alpert also recalls that the relationship between GKIDS and Ghibli started at the Children’s Film Festival. “They did a lot of the films that Disney wouldn’t screen theatrically,” he says. “That was how we first started working with them. And then it was just the question of getting rid of Disney. They had the rights to [the] contract. I think we always knew once the contract was done, we would probably dump them.”

And so just a few years after GKIDS was founded in 2008, the distributor officially teamed up with Studio Ghibli to begin releasing its catalog of films in theaters. This new partnership began with GKIDS’ creation of 35-mm film prints of Ghibli’s movies, which GKIDS used to present retrospectives first in New York and Los Angeles, and then across North America. GKIDS also agreed to distribute the second feature film directed by Goro Miyazaki (Hayao’s eldest son), 2011’s From Up on Poppy Hill, in North America. The company’s relationship with Studio Ghibli has snowballed from there.

“For a long time, when we started working on the [Ghibli] catalog, we were limited by actual logistics,” Jesteadt says. “Film prints are expensive. There’s only so many, so you cart them around. You generally play one theater per city. There’s just a lot of limitations. And so, when the theater industry changed over to digital, the DCP, that happened right around the time Ghibli Fest started. … That opened up a tremendous opportunity to say, ‘We no longer have to worry about our two or three film prints per movie. We can actually play a movie on 1,500 screens.’ And so there’s a scale thing that I think is really exciting.”

In 2017, GKIDS launched its first annual Studio Ghibli Fest in partnership with Fathom Events. Each year except 2020, GKIDS has worked with Ghibli to curate a carefully selected slate of the studio’s films to showcase to American audiences. As of late September, this year’s lineup had generated more than $13 million at the box office across 10 titles, with the annual event’s all-time total climbing to more than $40 million. (Howl’s Moving Castle earned more than $3 million in just five days in September; for comparison, the 2004 film earned $4.7 million in its original U.S. theatrical run.) Beyond box office margins, though, the Studio Ghibli Fests have given U.S. audiences the opportunity to rewatch, or experience for the first time, Miyazaki’s films, along with those from the studio’s talents who were never really introduced to non-Japanese audiences in the first place.

This year we ended up doing an all-Miyazaki lineup because we knew that we’d be launching The Boy and the Heron,” Jesteadt says. “And at the end of the year, we wanted to lay the groundwork for celebrating basically an entire career. But usually, we have a mix where there’s the big films and then perhaps some more rare films I think a lot of people aren’t familiar with. And we’re hoping that by putting them together, it creates a desire to go see Whisper of the Heart, or The Cat Returns, or The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, or Grave of the Fireflies.”

In addition to participating in the annual Ghibli Fests, the studio finally acquiesced to the modern appetite for streaming. After holding out for years, Ghibli and GKIDS agreed to a deal with Warner Bros. in 2019 that made HBO Max (now Max) the streaming home of Ghibli’s film library in the U.S. Even though it went against Ghibli’s preference for and dedication to the theatrical experience, the studio was willing to adapt to the times. “There are huge changes in terms of how audiences, not just in America but globally, are watching films,” Jesteadt says. “And some of that is for the worse, and some of it is good, but I think [Ghibli] definitely wanted to make sure that the younger generation discovered these films.

“There’s always felt like there’s been an untapped audience for these films, and in some ways removing barriers to access is ultimately really helpful to make sure that people do have a chance to experience them,” Jesteadt continues. “And even with playing Ghibli Fest, selling things on Blu-Ray, selling all the titles, even with the great numbers we were seeing, there’s still just a mass of people that were seeing films for the first time.”

With the release of The Boy and the Heron on Friday, audiences across the U.S. will all get the chance to experience that rare feeling of watching a brand-new Miyazaki feature film for the first time. It’s been 10 years since the last such opportunity, when 2013’s The Wind Rises arrived as what was then believed to be Miyazaki’s swan song. And with the new movie’s debut comes the chance to see a Miyazaki film not only in theaters, but on the biggest screen possible: The Boy and the Heron is the first Studio Ghibli film to be released simultaneously on IMAX and regular screens.

It took seven years for Miyazaki and 60 Studio Ghibli animators to complete The Boy and the Heron. Suzuki claims that it is probably the most expensive movie ever made in Japan, which feels fitting given the studio’s original priority to make good films above all else. In the wake of Ghibli’s sale to Nippon Television Holdings in September, and with no clear line of succession in place at the studio, there’s no telling what shape Ghibli will take when the 82-year-old Miyazaki can no longer keep producing masterpieces. But with the company’s long-term financial future secured and its decades’ worth of films made more accessible than ever around the world, Ghibli’s fan base should only continue to grow.