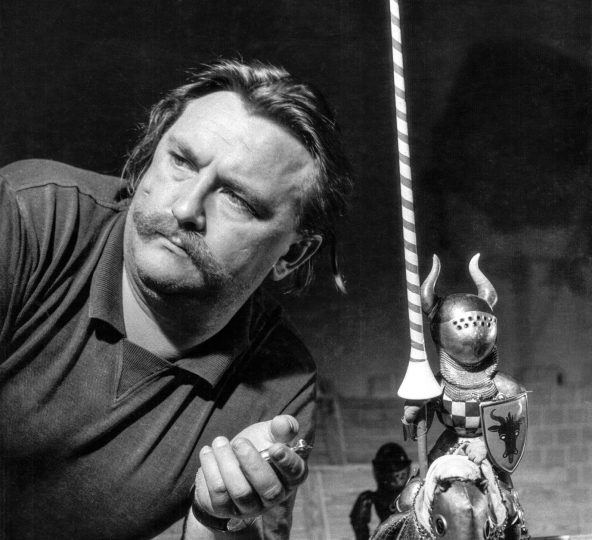

Jiří Trnka

Filed under: People, Animator, Artist, Cartoonist, Cinematographer, Illustrator, Painter, Puppeteer, Set Designer, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, Bratři v triku, Czech Republic, Fantasy, Jiří Trnka Studio, Puppetoons, Stop Motion, Studio kresleného a loutkového filmu, World War 2 ( WW2 ),

https://www.filmovyprehled.cz/cs/revue/detail/jiri-trnka-ve-filmech.

Full Name:Jiří Trnka

Occupation / Title:Animator, Artist, Cartoonist, Cinematographer, Illustrator, Painter, Puppeteer, Set Designer

Date of birth:24/02/1912

Date of death:30/12/1969

Birthplace:Pilsen, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (Plzeň, Czech Republic)

Associated studios:- Bratři v triku

- Studio kresleného a loutkového filmu

- Jiři Trnka Studio

Biography

Jiří Trnka was born in Pilsen (now Plzeň), Bohemia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire on February 24, 1912.

He was a Czech animator and illustrator who specialized in stop-motion puppetry animation. While he was known for illustrating children’s books, his animations were aimed toward mature audiences. He was dubbed as “the Walt Disney of Eastern Europe” due to his influence in the industry.

Trnka died in Prague, Czechoslovakia on December 30th, 1969.

Family and early life

Trnka’s interest in puppets can be traced back to his childhood (Dubská). Trnka was born to a family of artisans and craftspeople; his mother would create his first toys out of rags, and his grandparents were said to be woodcarvers who specialized in toys and figurines (Bellano, 26).

Trnka was mentored by Josef Skupa, a famous Czech puppeteer, who recognized and supported his talent (Dubská). He first encountered Skupa at his Holiday Camp Theatre in 1916, and would go on to become his pupil at a local high school (Bellano, 26–27).

Career outline

Trnka’s artistic career began shortly after winning a design competition organized by Josef Skupa in the early 1920s. He worked with Skupa for 10 years, dabbling in puppet carving and scene design (Bellano, 27).

From the mid-1930s to mid-1940s, Trnka worked as both a stage designer for the National Theatre in Prague and as a children’s book illustrator. In 1936, Trnka opened a modern puppet theatre of his own called “Dřevěné divadlo” (“Wooden Theatre”), but it did not last long as the performances were meant mostly for children (Dubská). Soon after, Trnka had his first encounter with cinema after Skupa asked him to create a puppet for an 1936 animated short called The Adventures of a Ubiquitous Fellow (Bellano, 30).

In 1945, Trnka began working in animation, producing Zasadil dĕdek repu (Grandpa Planted a Beet). He set up an animation unit at the Prague Film Studio called “Bratři v triku” (“Trick Brothers”) (Giesen and Bendazzi, 44). The Trick Brothers experimented with anti-fascist 2D animation, producing films such as Pérák a SS (Springman & the SS) (1946), before Trnka proposed a switch to stop-motion puppetry animation (Whybray, 44). His first film featuring puppets was the 1947 film Spalíček (The Czech Year). After the release of Spalíček, Trnka’s entire feature filmography used puppets as the main vehicles for stop-motion animation. Trnka favoured the medium over illustration due to its depth and more time-efficient production process (Polt, 37).

Personal style

Trnka’s puppets had particular traits made more pronounced so that they were more suitable for the camera; the puppets tended to have large heads and eyes, and their movement was far more limited compared to traditional theatre puppets. It is said that Trnka favoured stylization over naturalism when rendering scenes (Giesen and Bendazzi, 43).

Although caricatures, Trnka’s puppets still possessed a degree of softness. For instance, the puppet figurine used for Puck in Sen noci svatojánské (1959) had an anatomically consistent body, a carefully sculpted face, and a small mouth (Bellano, 27). This stylistic choice was different from his mentor’s, who intentionally created puppets with “weird” or dramatic appearances for enhanced comedic effect (Bellano, 27).

Trnka was also very conscious of his audience’s viewing experience. Even in climactic scenes, Trnka’s animation style was slow and contemplative, honouring his philosophy that animation should relax the spirit (Polt, 33).

Trnka’s films were also distinct in that they relied solely on music or spoken commentary, with The Good Soldier Schweik (1954–55) being the first time he let his puppets speak (Polt, 33).

Influences

It is speculated that working as a scene designer for Libuše (1939) caused Trnka to develop an interest in Czech and Bohemian folklore and music (Bellano, 33). He also fostered a strong relationship with composer Válclav Trojan, valuing the cinematographic potential of his music, which would be featured in Sen noci svatojánské (1959) (Bellano, 34).

Trnka was also inspired by politics. He used animation as a vessel to subtly communicate political and philosophical ideas, often in response to Nazism and the Soviet-style communism over Czechoslovakia (Whybray, 29). This is perhaps most evident in Trnka’s 1965 film titled Ruka (The Hand), which has been interpreted as an anti-Stalinist piece (Giesen and Bendazzi, 45).

Honors and awards

Zvířátka a Petrovští (Animals and Bandits) won Cannes Short Film of the Year in 1946.

Trnka is often referred to as the “Puppet Master” in writings and the press (Biography – Jiří Trnka).

Filmography

[Show/Hide]

References:

Bellano, Marco. “Jiří Trnka – Early Career and Relationship with Music.” Válclav Trojan, 1st ed., CRC Press, 2019, 23–38, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351122276-2.

“Biography – Jiři Trnka. IMDB, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0873240/bio/?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm. Accessed 19 July 2025.

Dubská, Alice. “Jiři Trnka.” World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts, 2012, https://wepa.unima.org/en/jiri-trnka/.

Giesen, Rolf, and Giannalberto Bendazzi. “Puppetoons versus Jiři Trnka.” Puppetry, Puppet Animation and the Digital Age, 1st ed., CRC Press, 2019, 35–52, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351209311-4.

“Jiři Trnka: Czech filmmaker. Britannica, n.d.

Jůn, Dominik. “Jiří Trnka: 100th anniversary of the birth of a great Czech animator.” Radio Prague International, 2012.

Polt, Harriet R.. “The Czechoslovak Animated Film.” Film Quarterly, vol. 177, no. 3, 1964, pp. 31–40. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1210908.

Whybray, Adam. “It’s the simple things’: Animated allegories against Nazi and Soviet oppression.” The Art of Czech Animation: A History of Political Dissent and Allegory, Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, 27–84, http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350104662.ch-001.