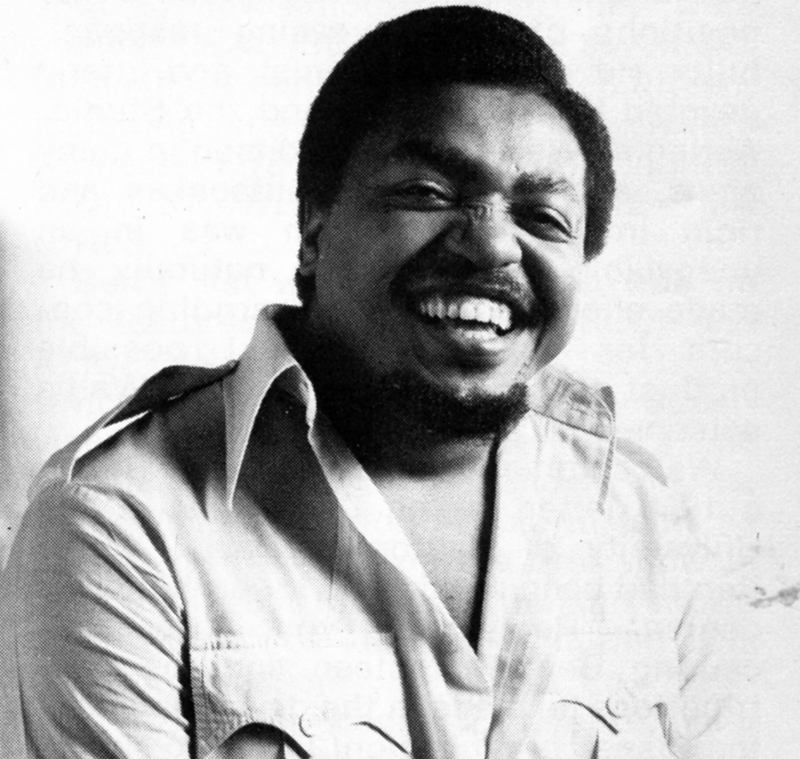

Jim Simon

Filed under: People, Animation Designer, Animator, Artist, Background Artist, Studio Head, Writer, 1970s, 1980s, Educational films, Paramount Pictures, Sesame Street, U.S.A.,

Full Name:

Full Name:James (Jim) A. Simon

Occupation / Title:Animation Designer, Animator, Artist, Background Artist, Studio Head, Writer

Date of birth:1950

Biography

Jim Simon is an artist and animator who created numerous commercials, public relation films, and entertainment and educational shorts during the 1970s and 1980s. Once dubbed “the Black Walt Disney” (even though he did not embrace the title), Simon was an outspoken animator on the industry’s unwelcoming attitude towards people of colour and representation in children’s programming. However many of his works are lost pieces of media.

Family and early life

When Simon was a child, his parents divorced, and his mother moved the family to Darlington, South Carolina. He later worked on his uncle’s cotton and tobacco farm in New York.

Simon has been married three times. His first marriage was with his high-school sweetheart Rene Simon, with whom he shared four boys.

Career outline

Upon graduation from the School of Visual Arts, Simon landed a job at Manhattan’s Paramount Pictures Cartoon division as a background artist/designer. However, four months after he started, Paramount closed its animation division in 1967. Simon followed his manager, Ralph Bakshi, to work as an Assistant Animator on the 1967 Spider-Man TV series. While Simon spent a year and a half as an Assistant Animator, he recalls accomplishing so much work that they had to promote him as he was earning more money than some of the animators. By 1970 Simon began freelance work as he dreamed of being a full-fledged animator.

While freelancing, in 1972, Simon went to Sesame Street to do animations for them. However, they told him he needed a company. So Simon borrowed $250 and hired a lawyer to set up his own company. He then returned to Sesame Street with five storyboards, and they accepted four of them. Simon’s animation company was named Wantu Studios.

Wantu is Swahili for ‘beautiful,’ and the symbol he used for the logo meant ‘new birth.’ Wantu was created to establish a Black presence in the animation scene that would produce work to reflect ‘the real America.’ Simon wanted Wantu to be a place that encouraged artists to grow. Hailed as the first all-African-American animation studio, Simon hired primarily Black artists. Only when there was a shortage of animators did he hire non-Black talent.

The first five years at Wantu Studios were highly successful, with perfect timing to the explosive growth of children’s education television. Wantu created about 90 animated short films in its first five years and received over 25 awards. By 1977 it was estimated that the company would produce around 50 projects a year with $400,00 gross sales. Wantu and Simon continued working for segments for Sesame Street, the Electric Company, and creating commercials. In the mid-1970s, Wantu began doing the bulk of animation segments for Vegetable Soup which was funded by the New York State Education Department that emphasised diversity.

Wanting to work on longer projects like Tv specials and feature films and growing tired of relying on commercial income, Simon took out a $47,000 loan and moved Wantu to Hollywood in early 1977. Less is known about Simon’s time once he moved to Hollywood. However, by the 1980s, he was forced to work for corporate studios.

During this time, he was involved in big productions like Yogi’s Space Race, the Smurfs, X-Men, Richie Rich, The Dukes, and Pac-Man. Some of Simon’s other projects included the title screen for the TV show Soul Train, character design on The New Archives, and creating the Brown Hornet segments for the Fat Albert cartoon series. Simon also went overseas (Ireland and Asia) as a supervisor or timing director on Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Doug, X-Men, and The Tick.

The 2000s were difficult for Simon as he suffered from depression, alcoholism, and homelessness. It was not until 2008 when a fellow artist, B.J. (Betty) Philips-Burton, inspired Simon to try oil pastels and portrait art. This inspiration led to his new art being featured for Black History Month at the St. Clair Gallery in El Cajon, San Diego, in 2009. Since then, in 2017, Simon did a retrospective of his career for Sacramento’s ArtStreet.

Personal style

Simon’s animations are known for his distinctive squiggly-lined style that featured African American characters. Black Enterprise magazine described his animation style as “Afro-cubistic realism.” In his animations, Simon did not use humanistic animal characters as he focused on a socially constructive model that drew from real life.

Simon was very vocal about the animation industry’s unwelcoming attitude toward people of colour. He criticized the lack of diversity in children’s programming with a network vice president in 1974 telling him that Black children were not considered a significant programming audience. The lack of diversity in children’s programming angered Simon.

During his career, Simon tried to develop several series including one with Don Cornelius entitled The Lil Soul Train and the Soul Kids. However, none of these ideas came to fruition.

Honors and awards

1975 – Animation Awards Festival the Animation Society of International Film Artists presented Wantu with 7 of 15 professional awards

1975 – World Animated Film Festival in Zagreb, Yugoslavia. Only 32 American films were being judged out of 130 entries (32 were Wantu)

References:

Animation Obsessive. “’A Loaf of Bread, a Container of Milk and a Stick of Butter’.” Animation Obsessive, 3 May 2021, https://animationobsessive.substack.com/p/a-loaf-of-bread-a-container-of-milk.

Garcia, Catherine. “Local Animator Makes a Comeback.” NBC 7 San Diego, 17 Feb. 2009, https://www.nbcsandiego.com/local/local-animator-makes-a-comeback/1890148/.

“Jim Simon – 1975.” Michael Sporn Animation – Splog, 24 Oct. 2008, http://www.michaelspornanimation.com/splog/?p=1638.

“Jim Simon.” Muppet Wiki, https://muppet.fandom.com/wiki/Jim_Simon.

Michalski, Thomas. “The (Forgotten) Black Walt Disney: Jim Simon.” HuffPost, 7 Dec. 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/jim-simon_b_1407924.

Simmons, Judy D. “Wantu Animation’s Jim Simon Makes His Mark in a $2 Billion-a-Year Industry .” Black Enterprise , May 1977, pp. 39–43.